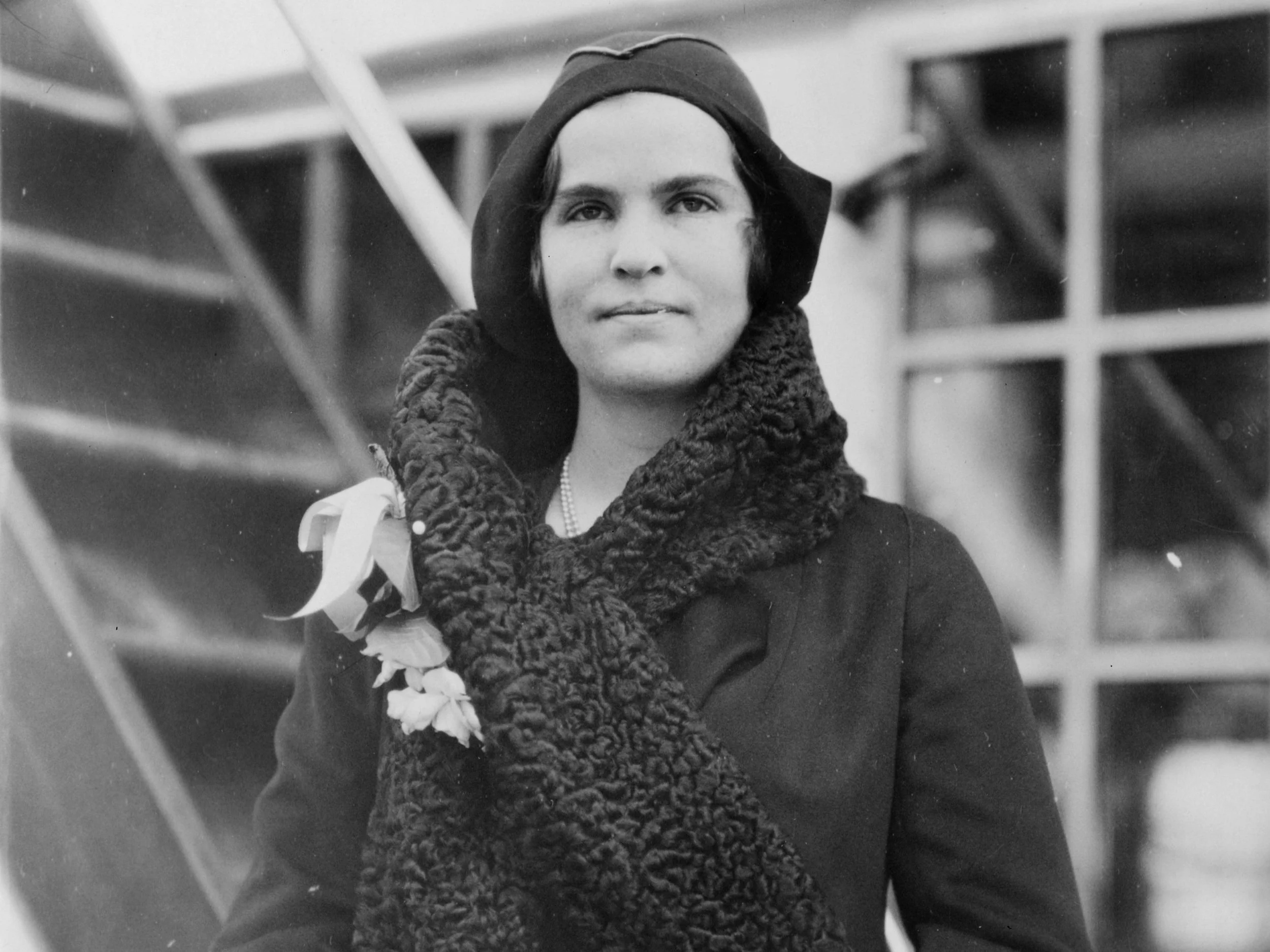

Elizabeth Hughes Gossett circa 1930

Elizabeth Hughes had a privileged upbringing that was unavailable to many. She was born in a large Queen Anne style mansion in Albany, New York on August 19, 1907. Her parents were Antoinette and Charles E. Hughes, the latter of whom eventually became the Secretary of State in the United States and the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. As a child, she was described as energetic and intellectually curious, often spending time alongside her sister, Helen.

In April 1919, Elizabeth was diagnosed with diabetes. Faced with a possibility of losing their daughter, Charles and Antoinette reluctantly agreed to send Elizabeth and her private nurse Blanche to Dr. Frederick Allen’s sanitarium, which eventually became the Psychiatric Institute in Morristown, New Jersey, as an in-patient for two years. Dr. Allen prescribed Elizabeth a strict diet of approximately 400 calories a day to manage her condition. This was the only method at the time that could reliably prolong the life of a person living with diabetes. Although Elizabeth’s survival was uncertain, she nevertheless remained optimistic, writing many letters to her “Dearest Mumsey” throughout her stay.

Slowly, however, she grew weaker with each passing month. By the time Antoinette had learned about the success of the insulin trials in July 1922, her once energetic daughter could barely walk and weighed a measly 48 pounds. To save her child, Antoinette wrote to Dr. Frederick Banting asking him to treat Elizabeth. Dr. Banting initially refused due to the already low supply of insulin but eventually agreed to examine her after much deliberation. In August of the same year, Elizabeth, Antoinette, and Blanche arrived in Toronto, where Dr. Banting administered her first dose of insulin. Slowly, she regained her weight and strength, eventually recovering enough to leave Toronto by December 1922.

Elizabeth would settle in Washington D.C. to complete high school before moving back to New York, graduating from Barnard College in 1929. A year later, she married William T. Gossett, a lawyer who worked in her father’s law firm. Eventually, they settled in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan and had three children. In Michigan, she volunteered for a variety of community, educational, and professional organizations.

Elizabeth’s life after treatment was paradoxical and complicated. After receiving treatment in Toronto, she sought to protect the normalcy that insulin gave her. She would feign confusion when asked about her childhood experiences with diabetes and would never involve herself with any causes related to the condition. She always arranged for her insulin to be sent to her secretly and removed any mention of her diabetes in her father’s papers and burned any photographs of her taken during her treatment. She would eventually die on April 21, 1981, having received approximately 42,000 doses of insulin in 58 years. At the time of her death, very few knew that she had diabetes, which only became public knowledge after her grandson revealed her condition in 1982.

— Written by Michael Limmena